Using Options as Shares of Stock

By Bill Johnson

Options are powerful. Options are versatile. But some stock traders are convinced that options are risky, and they continue to trade stock that puts them at a disadvantage. For this article, let’s take a look at how options can be used as shares of stock.

To master options trading, you must understand that it’s the option’s time value that makes it an option. If an option is made up entirely of intrinsic value and now time value, it’s not an option – it’s stock. For example, let’s say one trader buys shares of stock trading for $110, but another buys a $100 call trading for $10. That call’s price is entirely intrinsic value – the difference between the $110 stock price and the $100 strike. In options trading terms, this option is trading at parity, which means it’s equivalent to shares of stock.

To see why, pick any stock price above the $100 strike, and the $100 call owner and stock owner will perform identically. If the stock is $115, the stock buyer makes $5 and so does the call buyer. If the stock is $130, both traders make $20. On the other hand, if the stock price drops to the $100 strike, the options trader and stock trader both lose $10 – again, neither trader better or worse off than the other.

However, if the stock price falls below the $100 strike, that relationship changes, and the options trader will outperform the stock buyer. The options trader can’t lose any more than the initial $10 paid, but the stock buyer continues to lose. In other words, if the stock price falls below the $100 strike, you’re better off holding the option. By holding the shares of stock, you can’t do better – but you could do worse. There is a benefit in holding the option, and that’s why you’ll usually pay a time value. It’s the price the option’s buyer pays for the protection of losses below the strike.

In the real world of trading, it’s rare to see an option trading for parity, except when the option is about to expire. However, by choosing an option strike that’s deep in the money, you can greatly reduce the time value and therefore make the option behave nearly identical to the shares of stock – but with big benefits.

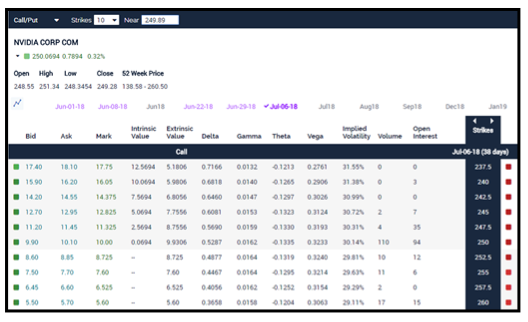

For instance, on June 25, Home Depot (HD) closed at $196.38. If you wanted to buy 100 shares, it would cost nearly $20,000. However, the January 2019 $150 call with 207 days to expiration was trading for $48.38. The breakeven price $198.38 – exactly $2 greater than the current stock price. That additional $2 is the time value, which provides the insurance against losses should the stock’s price fall below the $150 strike at expiration.

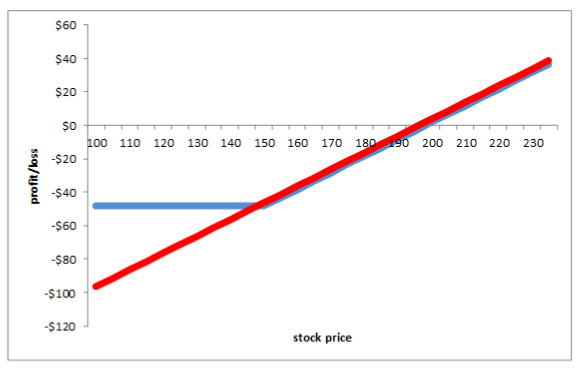

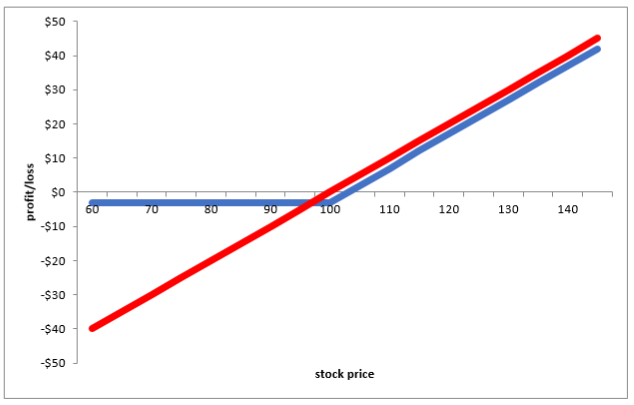

Pick any stock price above the $150 strike, and the option buyer just gives up the $2 time value compared to the stock trader. If the stock price falls below $148, the option buyer outperforms the stock buyer. In the chart below, you can see there’s very little difference between the red line (stock) and the blue line ($150 call) for all stock prices above $148. The two lines nearly overlap and are only separated by the $2 time value. However, below $148, the stock trader continues to take losses whereas the options trader’s loss is limited to the $48.38 premium paid:

Now consider the benefits. By paying $48.38 for the call, you’re spending less than 25% of the stock’s price. The best leverage you can get as a stock trader is 25% – and but you must close the position by the end of the day. The options trader, however, may continue to hold. Further, the options trader will never pay margin interest or receive a maintenance call. The options trader has more money to diversify into other trades – or average into positions across time. These are all things the stock trader cannot do as efficiently, but it only cost the options trader the $2 time value.

Options don’t have to be options. By understanding the art and science of options trading, you can make options behave like shares of stock– but for far less cost and much bigger advantages.

Good Investing!

Bill Johnson, Steve Bigalow

and The Candlestick Forum Team

P.S. Bill Johnson’s Alpha Trader Options Course takes you from the very beginning, step-by-step, through an exciting journey into the world of options. At the end, you’ll have the necessary knowledge and confidence to start investing and hedging with options. In addition, you’ll have a rock-solid foundation from which to continue your options education.

Trading in the Stock Market, Trading Options, Trading Futures, and Options on Futures, involves substantial risk of loss and is not suitable for all investors. Past Performance is not indicative of future results. CandlestickForum.com, Candlestick-Trading-Forum.com, StephenBigalow.com, and Candlestick Forum LLC do not recommend or endorse any specific trading system or method. We recommend that you research all trading systems, methods and market strategies thoroughly. Full Disclaimer here